Conclusion to The Play’s the Thing

Part One

By Dennis Abrams

It’s hard to believe it’s been two and half years since we started our journey through Shakespeare’s plays. For me, it’s been incredibly educational, fulfilling, inspiring, and downright fun. In my last post I’m going to share my final thoughts on all the plays, but for today, I have to give you my beloved Harold Bloom, and his coda to Shakespeare: The Invention of the Human, “The Shakespearean Difference,” which I think is direct to the point:

“If there is validity to my surmise that Shakespeare, by inventing what has become the most accepted mode for representing character and personality in language, thereby invented the human as we know it, then Shakespeare also would have modified severely our ideas concerning our sexuality. The late Joel Fineman, questing to understand Shakespeare’s ‘subjectivity effect,’ found in the Sonnets a paradigm for all of Shakespeare’s (and literature’s) bisexualities of vision. Setting aside Fineman’s immersion in the critical fashions that ascribe everything to ‘language’ rather than to the authorial self, he nevertheless had an authentic insight into the link between Shakespeare’s portraits of an ever-growing inner self, and Shakespeare’s preternatural awareness of bisexuality and its disguises.

“If there is validity to my surmise that Shakespeare, by inventing what has become the most accepted mode for representing character and personality in language, thereby invented the human as we know it, then Shakespeare also would have modified severely our ideas concerning our sexuality. The late Joel Fineman, questing to understand Shakespeare’s ‘subjectivity effect,’ found in the Sonnets a paradigm for all of Shakespeare’s (and literature’s) bisexualities of vision. Setting aside Fineman’s immersion in the critical fashions that ascribe everything to ‘language’ rather than to the authorial self, he nevertheless had an authentic insight into the link between Shakespeare’s portraits of an ever-growing inner self, and Shakespeare’s preternatural awareness of bisexuality and its disguises.

Here, as ever, Shakespeare is the original psychologist, and Freud the belated rhetorician. The human endowment, Shakespeare keeps intimating, is bisexual: after all, we have both mothers and fathers. Whether we ‘forget’ either the heterosexual or the homosexual component in our desire, or ‘remember’ both, is in the Sonnets in the plays not a question of choice, and only rarely a matter of anguish. Antonio’s melancholy in The Merchant of Venice seems the largest exception, since his sorrow at losing Bassanio to Portia has suicidal overtones. Shakespeare was, at the least, a skeptical ironist, and so his representations of bisexuality hardly could forgo an ironic reserve, more ambiguous than ambivalent.

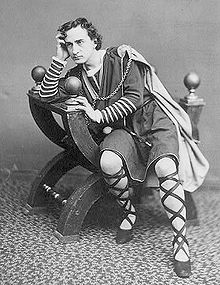

Nietzsche ambiguously followed Hamlet in telling us that we could find words only for what was already dead in our hearts, so that there was always a kind of contempt in the act of speaking. Before Hamlet taught us how not to have faith either in language or in ourselves, being human was much simpler for us but also rather less interesting. Shakespeare, through Hamlet has made us skeptics in our relationships with anyone, because we have learned to doubt articulateness in the realm of affection. If someone can say too readily or too eloquently how much they love us, we incline not to believe them, because Hamlet has gotten into us, even as he inhabited Nietzsche.

Our ability to laugh at ourselves as readily as we do at others owes much to Falstaff, the cause of wit in others as well as being witty in himself. To cause wit in others, you must learn how to be laughed at, how to absorb it, and finally how to triumph over it, in high good humor. Dr. Johnson praised Falstaff for his almost continuous gaiety, which is accurate enough but neglects Falstaff’s overt desire to teach. What Falstaff teaches us is a comprehensiveness of humor that avoids unnecessary cruelty, because it emphasizes instead the vulnerability of every ego, including that of Falstaff himself.

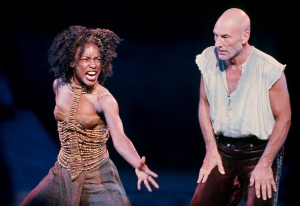

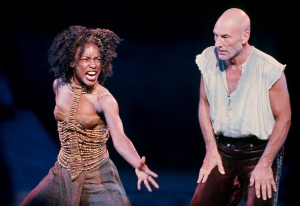

Shakespeare’s wisest woman may be Rosalind in As You Like It, but his most comprehensive is Cleopatra, through whom the playwright taught us how complex eros is, and how impossible it is to divorce acting the part of being in love and the reality of being in love. Cleopatra brilliantly bewilders us, and Antony, and herself. Mutability is incessant in her passional existence, and it excludes sincerity as being irrelevant to eros. To be more human in love is, now, to imitate Cleopatra, whose erotic variety make staleness impossible, and certitude just as unlikely.

Shakespeare’s wisest woman may be Rosalind in As You Like It, but his most comprehensive is Cleopatra, through whom the playwright taught us how complex eros is, and how impossible it is to divorce acting the part of being in love and the reality of being in love. Cleopatra brilliantly bewilders us, and Antony, and herself. Mutability is incessant in her passional existence, and it excludes sincerity as being irrelevant to eros. To be more human in love is, now, to imitate Cleopatra, whose erotic variety make staleness impossible, and certitude just as unlikely.

Four centuries have only augmented Shakespeare’s universal influence; it seems accurate to observe that many more have read the plays, for themselves or in schools, than have attended performances, or even seen versions in movie houses and on television. Will that change in the new century, since deep reading is in decline, and Shakespeare, as the Western canon’s center, now vanishes from the schools with the canon? Will generations to come believe current superstitions, and so cast away genius, on the grounds that all individuality is an illusion? If Shakespeare is only a product of social processes, perhaps any social product will seem as good as any other, past or present. In the culture of virtual reality, partly prophesied by Aldous Huxley, and in another way by George Orwell, will Falstaff and Hamlet still seem paradigms of the human? A journalist, scorning what he called any ‘lone genius,’ recently proclaimed that the three leading ‘ideas’ of our moment were feminism, environmentalism, and structuralism. That is to mistake political and academic fashions for ideas, and stimulates me to ask again, Who besides Shakespeare can continue to inform an authentic idea of the human?

Had Shakespeare been murdered at twenty-nine, like Christopher Marlowe, then his career would have ended with Titus Andronicus or the Taming of the Shrew and his masterpiece would have been Richard III. Social processes would have courses on under Elizabeth and then under James, but the twenty-five plays that matter most would not have come out of Renaissance Britain. Cultural poetics doubtless could be as well occupied with George Chapman or Thomas Heywood, since a social energy is a social energy, if that is your standard for value or concern. We all of us might be gamboling about, but without mature Shakespeare we would be very different, because we would think and feel and speak differently. Our ideas would be different, particularly our ideas of the human, since they were, more often than not, Shakespeare’s ideas before they were ours. That is why we do not have feminist Chapman, structuralist Chapman, and environmentalist Chapman, and may yet, alas, have environmentalist Shakespeare.

Shakespeare has had the status of a secular Bible for the last two centuries. Textual scholarship on the plays approaches biblical commentary in scope and intensiveness, while the quantity of literary criticism devoted to Shakespeare rivals theological interpretation of Holy Scripture. It is no longer possible for anyone to read everyone of some interest and value that has been published on Shakespeare. Though there are indispensible critics of Shakespeare – Samuel Johnson, William Hazlitt, perhaps Samuel Taylor Coleridge – certainly A.C. Bradley – most commentary upon Shakespeare at best answers the needs of a particular generation in one country or another. Those needs vary: directors and actors, audiences and common readers, scholar-teachers and students do not necessarily seek the same aids for understanding. Shakespeare is an international possession – transcending nations, languages, and professions. More than the Bible, which competes with the Koran, and with Indian and Chinese religions writings, Shakespeare is unique in the world’s culture, not just in the world’s theaters.

This book – Shakespeare: The Invention of the Human – is a latecomer work, written in the wake of Shakespeare critics I most admire: Johnson, Hazlitt, Bradley, and their mid-twentieth century disciple, Harold Goddard. I have sought to take advantage of my belatedness by asking always, Why Shakespeare? He already was the Western canon, and is now becoming central to the world’s implicit canon. As I assert throughout, Hamlet and Falstaff, Rosalind and Iago, Lear and Cleopatra are clearly more than great roles for actors and actresses. It is difficult sometimes not to assume that Hamlet is as ancient a hero as Achilles or Oedipus, or not to believe that Falstaff was as historical a personality as Socrates. When we think of the Devil, we are as likely to reflect on Iago as on Satan, while the historical Cleopatra seems only a shadow of Shakespeare’s Egyptian mesmerizer, the Fatal Woman incarnate.

Shakespeare’s influence, overwhelming on literature, has been even larger on life, and thus has become incalculable, and seems recently only to be growing. It surpasses the effect of Homer and of Plato, and challenges the scriptures of West and East alike in the modification of human character and personality. Scholars who wish to confine Shakespeare to his context – historical, social, political, economic, rational, theatrical – may illuminate particular aspects of the plays, but are unable to explain the Shakespearean influence on us, which is unique, and which cannot be reduced to Shakespeare’s own situation, in his time and place.

If the world indeed can have a universal and unifying culture, to any degree of notice, such a culture cannot emanate from religion. Judaism, Christianity, and Islam have a common root, but are more diverse than similar, and the other great religious traditions, centered upon China and India, are very remote from the Children of Abraham. The universe increasingly has a common technology, and in time may constitute one vast computer, but that will not quite be a culture. English already is the world language, and presumably will become even more so in the twenty-first century. Shakespeare, the best and central writer in English, already is the only universal author, staged and read everywhere. There is nothing arbitrary in this supremacy. Its basis is only one of Shakespeare’s gifts, the most mysterious and beautiful: a concourse of men and women unmatched in the rest of literature. Iris Murdoch, whose high but impossible ambition has to become a Shakespearean novelist, once told an interviewer, ‘There is of course the great problem – to be able to be like Shakespeare – create all kinds of different people quite unlike oneself.’

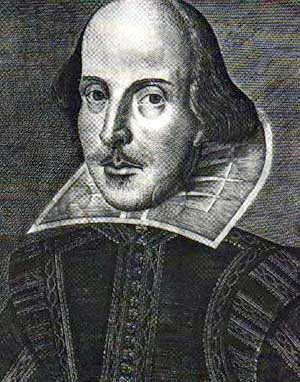

What Shakespeare was like, we evidently never will know. We may be incorrect in believing we know what Ben Jonson and Christopher Marlowe were like, and yet we seem to have a clear sense of their personalities. With Shakespeare, we know a fair number of externals, but essentially we know absolutely nothing. His deliberate colorlessness may have been one of his many masks for an intellectual autonomy and originality so vast that not only his contemporaries but also his forerunners and followers have been considerably eclipsed by comparison. One hardly can overstress Shakespeare’s inward freedom; it extends to the conventions of his era, and to those of the stage as well. I think we need to go further in recognizing this independence than we ever have done. You can demonstrate that Dante or Milton or Proust were perfected products of Western civilization, as it had reached them, so that they were both summits and epitomes of European culture at particular times and particular places. No such demonstration is possible for Shakespeare, and not because of any supposed ‘literary transcendence.’ In Shakespeare, there is always a residuum, an excess that is left over, no matter how superb the performance, how acute the critical analysis, how massive the scholarly accounting, whether old-style or newfangled. Explaining Shakespeare is an infinite exercise; you will become exhausted long before the plays are emptied out. Allegorizing or ironizing Shakespeare by privileging cultural anthropology or theatrical history or religion or psychoanalysis or politics or Foucault or Marx or feminism works only in limited ways. You are likely, if you are shrewd, to achieve Shakespearean insights into your favorite hobbyhorse, but you are rather less likely to achieve Freudian or Marxist or feminist insight into Shakespeare. His individuality will defeat you; his plays know more than you do, and your knowingness consequently will be in danger of dwindling into ignorance.

Can there be a Shakespearean reading of Shakespeare? His plays read one another, and a double handful of critics have been able to follow the plays in that project. I would like to believe that there could still be a Shakespearean staging of Shakespeare, but is quite a long time now since I last encountered one. This book offers what is intends as a Shakespearean reading of the characters of his plays, partly by employing one character to interpret another. Sometimes, I have resorted to a few characters by other authors, particularly by Chaucer and Cervantes, but going outside Shakespeare to apprehend Shakespeare better is a dangerous procedure, even if you confine yourself to the handful or fewer of writers who are not destroyed by being compared with the creator of Falstaff and of Hamlet. Juxtaposing Shakespeare’s characters to those of his contemporary and rival dramatists is ludicrous, as I have indicated throughout this book. Literary transcendence is now out of fashion, but Shakespeare so transcends his fellow playwrights that critical absurdity hovers near when we seek to confine Shakespeare to his time, place, and profession. These days, critics do not like to begin by standing in awe of Shakespeare, but I know of no other way to begin with him. Wonder, gratitude, shock, amazement are the accurate responses out of which one has to work.

Jacob Burkhardt, a rather distinguished Old Historicist, has just one mention of Shakespeare in his masterwork, The Civilization of the Renaissance in Italy (1860), but is quite devastating to Renaissance Italy, and to its Spanish overlords. That Shakespeare’s timing and location were immensely fortunate has to be granted, but then several other dramatists in his generation had the same advantages. Burckhardt’s true point was ‘that such a mind is the rarest of heaven’s gifts.’ Together with his younger colleague at Basel, Friedrich Nietzsche, Jacob Burkhardt revived for us the ancient Greek sense of the agnostic, the vision of literature as an incessant and ongoing contest. Shakespeare, though he has to begin by absorbing and then struggling against Marlowe, became so strong with the creation of Falstaff and Hamlet that it is difficult to think of him as competing with anyone, once he had fully individuated. From Hamlet on, Shakespeare’s contest primarily was with himself, and the evidence of the plays and their likely compositional sequence indicates that he was driven to outdo himself.

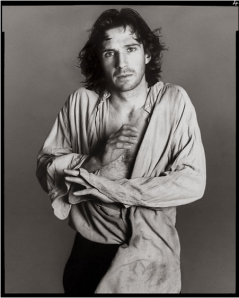

Charles Lamb, admirable critic, has been much denigrated in this century for insisting that it was better to read Shakespeare than to watch him acted. If one could be certain that Ralph Richardson or John Gielgud or Ian McKellan was to do the acting, then argument with lamb would be possible. But to see Ralph Fiennes, under bad direction, play Hamlet as a poor little rich boy, or to sustain George C. Wolfe’s skilled travesty of The Tempest, is to reflect upon Lamb’s wisdom. When you read, then you can direct, act, and interpret for yourself (or with the help of Hazlitt, A.C. Bradley, and Harold Goddard). In the theater, much of the interpreting is done for you, and you are victimized by the politic fashions of the moment. Harry Berger, Jr., in a wise book, Imaginary Audition (1989) gives us a fine irony:

Charles Lamb, admirable critic, has been much denigrated in this century for insisting that it was better to read Shakespeare than to watch him acted. If one could be certain that Ralph Richardson or John Gielgud or Ian McKellan was to do the acting, then argument with lamb would be possible. But to see Ralph Fiennes, under bad direction, play Hamlet as a poor little rich boy, or to sustain George C. Wolfe’s skilled travesty of The Tempest, is to reflect upon Lamb’s wisdom. When you read, then you can direct, act, and interpret for yourself (or with the help of Hazlitt, A.C. Bradley, and Harold Goddard). In the theater, much of the interpreting is done for you, and you are victimized by the politic fashions of the moment. Harry Berger, Jr., in a wise book, Imaginary Audition (1989) gives us a fine irony:

‘It is no doubt perverse to find that desire of theater burning through Shakespeare’s texts is crossed by a certain despair of theater, of the theater that seduces them and the theater they seduce; a despair inscribed in the auditory voyeurism with which the spoken language outruns its auditors, dropping golden apples along the way to divert the greedy ear that longs to devour its discourse.’

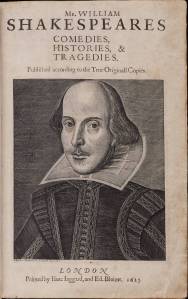

Presumably, this ironic perversity stems from Shakespeare’s apparent fecklessness as to the survival of his plays’ texts. The creative exuberance of Shakespeare doubtless suggested carelessness to the superbly labored Ben Jonson, at least in some of his moods, but ought not to mystify us. There is indeed a bad current fashion among some Shakespearean scholars to reduce the post-dramatist to the crudest texts that somehow can be deemed authentic. Sir Frank Kermode has protested eloquently against this destructive practice, which can be seen at its worst in the Oxford Editions of Gary Taylor. Charles Lamb was amiably seconded by Rosalie Colie, who reminded us of the advice given by the editors of the First Folio, Shakespeare’s fellow actors, Heminges and Condell. ‘Read him, therefore, and againe, and againe.’ Cole added the fine reminder that ‘no excuse is needed for treating Chaucer’s work as read material, although we know he read it aloud, as performance, at the time.’

Presumably, this ironic perversity stems from Shakespeare’s apparent fecklessness as to the survival of his plays’ texts. The creative exuberance of Shakespeare doubtless suggested carelessness to the superbly labored Ben Jonson, at least in some of his moods, but ought not to mystify us. There is indeed a bad current fashion among some Shakespearean scholars to reduce the post-dramatist to the crudest texts that somehow can be deemed authentic. Sir Frank Kermode has protested eloquently against this destructive practice, which can be seen at its worst in the Oxford Editions of Gary Taylor. Charles Lamb was amiably seconded by Rosalie Colie, who reminded us of the advice given by the editors of the First Folio, Shakespeare’s fellow actors, Heminges and Condell. ‘Read him, therefore, and againe, and againe.’ Cole added the fine reminder that ‘no excuse is needed for treating Chaucer’s work as read material, although we know he read it aloud, as performance, at the time.’

Shakespeare directing Shakespeare, at the Globe, hardly could supervise performances of Hamlet or King Lear in their full, bewildering perplexities. As director, even Shakespeare had to choose to emphasize one perspective or another, the limitation of every director and of every actor. With dramas almost infinite in their amplitude, Shakespeare (with whatever suffering, or whatever unconcern) had to reduce the range of possible interpretation. The critical reading of Shakespeare, not by academics but by the authentic enthusiasts in his audience, had to have begun as a contemporary concern, since those early quartos – good and bad – were offered for sale, sold, and reprinted. Eighteen of Shakespeare’s plays had appeared in separate volumes before the First Folio of 1623, starting with Titus Andronicus in 1594, the year of its first performance, when Shakespeare turned thirty. Falstaff’s advent (under his original name, Oldcastle), in 1598, was attended by two quarto printings, with reprintings in 1599, 1604, 1608, 1613, and 1622, and two more quartos followed the First Folio in 1632 and 1639. Hamlet, Falstaff’s only rival in contemporary popularity, sustained two quartos within two years of his first stage appearance. The point is that Shakespeare knew he had early readers, less numerous by far than his audience, but more than just a chosen few. He wrote primarily to be aced, yes, but he wrote also to be read, by a more select group. This is not to suggest that there are two Shakespeares, but rather to remind us that the one Shakespeare was subtler and more comprehensive than certain reductionists care to acknowledge.

William Hazlitt, in 1814, wrote a brief essay called ‘On Posthumous Fame – Whether Shakespeare Was Influence by a Love of It?’ One can wonder at Hazlitt’s conclusion, which was that Shakespeare was wholly free of such egotism. Nowadays, many critics like to think of Shakespeare as the Andrew Lloyd Webber of his day, coining money and allowing posterity to care for itself. This seems very dubious to me. Shakespeare was not Ben Jonson, but he was much in Jonson’s company, and probably he had too keen a sense of his own powers to share in Jonson’s or George Chapman’s anxieties about literary survival. The Sonnets of Shakespeare are very divided on this, as on most matters, but the aspiration for literary permanence figures strongly in them. Perhaps Coleridge, in his transcendental intensity, got this best: ‘Shakespeare is the Spinozistic deity – an omnipresent creativeness.’

Spinoza said that we should love God without expecting that God would love us in return. Perhaps Shakespeare, as such a godhead, accepted his audience’s homage without giving it anything in return, perhaps indeed Hamlet is Shakespeare’s authentic surrogate, provoking the audience’s love precisely because Hamlet palpably does not need or want its love, or anyone’s love. Shakespeare may not have been strong enough not to need the poet-dramatist’s equivalent of love, an intimation of the applause of eternity. Yet so ruthless an experimenter, who increasingly declined to repeat himself, who used the old almost always to make something radically new, seems as a playwright to have consistently quested for his own inward interests, even as he took care to stay ahead of the competition. The essence of poetry, according to Dr. Johnson, was invention, and no poetry that we have approaches Shakespeare’s plays as invention, particularly as invention of the human.

There is the heart of the matter, at once the subject of this book and the mark of my difference from nearly all current Shakespearean criticism, whether academic, journalistic, or theatrical. It is most possible that Shakespeare was unaware of his originality at the representation of human nature – that is to say, of human action, and the way such action frequently was antithetical to human words. Marlowe and Jonson, in their different but related ways, can be said to have valued words over action, or perhaps rather to have seen the playwright’s proper function as showing that words were the authentic form of action. Shakespeare’s apparent skepticism, the opening mark of his difference from Marlowe and Jonson alike, asks us to observe that we act very unlike our words. The central principle of Shakespearean representation at first seems a more-then-Nietzschean skepticism, since Hamlet knows that what he can find words for is already dead in his heart, and consequently he scarcely can speak without contempt for the act of speaking. Falstaff, who gives all to wit, can speak without contempt, but he speaks always with ironies that transcend even his pupil Hal’s full apprehension. Sometimes I reflect that not Hamlet and Falstaff, but Iago and Edmund are the most Shakespearean characters, because in them, and by them, the radical gap between words and action is most fully exploited. Skepticism, as a term fits Montaigne or Nietzsche better than it does Shakespeare, who cannot be confined to a skeptical stance, however widely (or wildly) we define it. The best analyst of this Shakespearean freedom has been Graham Bradshaw, in his admirable Shakespeare’s Skepticism (1987), one of the half-dozen or so best modern (since A.C. Bradley, that is) books about Shakespeare.

There is the heart of the matter, at once the subject of this book and the mark of my difference from nearly all current Shakespearean criticism, whether academic, journalistic, or theatrical. It is most possible that Shakespeare was unaware of his originality at the representation of human nature – that is to say, of human action, and the way such action frequently was antithetical to human words. Marlowe and Jonson, in their different but related ways, can be said to have valued words over action, or perhaps rather to have seen the playwright’s proper function as showing that words were the authentic form of action. Shakespeare’s apparent skepticism, the opening mark of his difference from Marlowe and Jonson alike, asks us to observe that we act very unlike our words. The central principle of Shakespearean representation at first seems a more-then-Nietzschean skepticism, since Hamlet knows that what he can find words for is already dead in his heart, and consequently he scarcely can speak without contempt for the act of speaking. Falstaff, who gives all to wit, can speak without contempt, but he speaks always with ironies that transcend even his pupil Hal’s full apprehension. Sometimes I reflect that not Hamlet and Falstaff, but Iago and Edmund are the most Shakespearean characters, because in them, and by them, the radical gap between words and action is most fully exploited. Skepticism, as a term fits Montaigne or Nietzsche better than it does Shakespeare, who cannot be confined to a skeptical stance, however widely (or wildly) we define it. The best analyst of this Shakespearean freedom has been Graham Bradshaw, in his admirable Shakespeare’s Skepticism (1987), one of the half-dozen or so best modern (since A.C. Bradley, that is) books about Shakespeare.

For Bradshaw, Shakespeare’s mastery of ironic distancing is one of the poet-dramatist’s central gifts, creating a pragmatic skepticism in regard to all questions of ‘natural’ value. I would alter this only by swerving away from such skepticism, as I think Shakespeare himself did, by giving up all rival accounts of nature through an acceptance of the indifference of nature. We can surmise that Shakespeare, with nature’s largeness in him, testified to nature’s indifference, and so at last to death’s indifference. Yet Shakespeare, with art’s greater largeness also in him, is neither indifferent nor quite skeptical, neither a believer nor a nihilist. His plays persuade all of us that they care, that their characters do matter, but never for, or to, Eternity.

Sometimes these personages matter to others, but always finally to themselves – even Hamlet, even Edmund, even the wretched Parolles of All’s Well That Ends Well and the rancid Thersites of Troilus and Cressida. Value in Shakespeare, as Jane Austen admirably learned from him, is bestowed upon one character by or through another or others and only because of the hope of shared esteem. We are skeptical of Hamlet’s final estimate of Fortinbras, even as we are somewhat quizzical as to Hamlet’s perpetual overestimation of the faithful but colorless Horatio. We are not at all skeptical of Hamlet’s own value, despite his own despair of it, because everyone in the play even Hamlet’s enemies, somehow testifies to it.

We cannot get enough perspectives on Hamlet, and always want still more, because Hamlet’s largeness and his indifference do not so much merge him into nature as they confound nature with him. Falstaff’s equal circumference of consciousness suggests that nature can achieve mind only by associating itself with Falstaff, and thus acquiring something of his wit. Edmund mistakenly invokes nature as his goddess, whereas his actual, negative achievement is to tender nature into a devouring entity, a mind (of sorts) that excludes very nearly all affect. Iago, more accurately invoking a ‘divinity of hell,’ succeeds in his brilliant project of destroying the only ontological reality he knows, organized warfare, as epitomized by the war god Othello, and replacing it with an anarchic incessant warfare of all against all. Iago does this in the name of a nothingness that can compensate him for his own wound, his sense of having been passed over and rejected by the only value he has ever known, Othello’s martial glory.

We cannot get enough perspectives on Hamlet, and always want still more, because Hamlet’s largeness and his indifference do not so much merge him into nature as they confound nature with him. Falstaff’s equal circumference of consciousness suggests that nature can achieve mind only by associating itself with Falstaff, and thus acquiring something of his wit. Edmund mistakenly invokes nature as his goddess, whereas his actual, negative achievement is to tender nature into a devouring entity, a mind (of sorts) that excludes very nearly all affect. Iago, more accurately invoking a ‘divinity of hell,’ succeeds in his brilliant project of destroying the only ontological reality he knows, organized warfare, as epitomized by the war god Othello, and replacing it with an anarchic incessant warfare of all against all. Iago does this in the name of a nothingness that can compensate him for his own wound, his sense of having been passed over and rejected by the only value he has ever known, Othello’s martial glory.

Shakespeare’s representation of the human is not a return to nature, despite the startled sense that has prevailed from Shakespeare’s contemporaries to the present, which is that Shakespeare’s men, woman, and children are somehow more ‘natural’ than other dramatic and literary characters. If you believe, as so many apostles of ‘cultural studies’ assert they do, that the natural ego is an obsolete entity, and that individual style is an outmoded mystification, then Shakespeare, like Mozart or Rembrandt, is likely to seem interesting primarily for qualities that all artists share, whatever their relative eminence. Disbelief in a self o one’s own is a kind of elitist secular heresy, perhaps only available to the sect of ‘cultural studies.’ The death of the author, Foucault’s post-Nietzschean invention, convinces academic partisans gathered under Parisian banners, but means nothing to the leading poets, novelists, and dramatists of our moment, who almost invariably assure us that their quest is to develop further their own selfish innovations. I don’t want to blame postmodernist Paris upon Freud, but I suspect that the master’s sublime confidence at inventing inner agencies, and ascribing independent existence to such gorgeous fictions, is the foreground to the ‘death of the subject’ in the poststructural prophets of Resentment. If the ego can be predicated or voided with equal ease, then selves can be shuffled off with high cultural abandon.

What happens to Sir John Falstaff if we deny him an ego? The question is doubly funny, since some of us would shrug and say, ‘After all, he is just language,’ and a few of us might want to say that the vivid representation of so strong a selfhood dismisses all skepticism as to the reality of the ego. Sir John himself certainly feels no self-skepticism; his gusto precludes Hamletian waverings as to whether we are too full or too empty. There is an abyss of potential loss in Falstaff; he senses that he will die of betrayed affection. Empson, determined not to be sentimental about fat Jack, wanted us to think of the great comedian as a dangerously powerful Machiavel. Empson was a great critic, but nevertheless he forgot that Shakespeare’s major Machiavels – Iago and Edmund – know themselves to be ontologically nil, which is not exactly a Falstaffian malady. In vitalistic self-awareness, Falstaff surely is the Wife of Bath’s child. He would have liked Henry V to fill his purse, but his killing grief at being rejected is not primarily a worldly catastrophe.

What happens to Sir John Falstaff if we deny him an ego? The question is doubly funny, since some of us would shrug and say, ‘After all, he is just language,’ and a few of us might want to say that the vivid representation of so strong a selfhood dismisses all skepticism as to the reality of the ego. Sir John himself certainly feels no self-skepticism; his gusto precludes Hamletian waverings as to whether we are too full or too empty. There is an abyss of potential loss in Falstaff; he senses that he will die of betrayed affection. Empson, determined not to be sentimental about fat Jack, wanted us to think of the great comedian as a dangerously powerful Machiavel. Empson was a great critic, but nevertheless he forgot that Shakespeare’s major Machiavels – Iago and Edmund – know themselves to be ontologically nil, which is not exactly a Falstaffian malady. In vitalistic self-awareness, Falstaff surely is the Wife of Bath’s child. He would have liked Henry V to fill his purse, but his killing grief at being rejected is not primarily a worldly catastrophe.

Is it possible to account for Shakespeare’s universalism, for our sense of his uniqueness? I grant that America’s Shakespeare is not Britain’s, nor Japan’s, nor Norway’s, but I recognize also something that really is Shakespeare’s, and that always survives his successful migration from country to country. Against all of our current demystifications of cultural eminence, I go on insisting that Shakespeare invented us (whoever we are) rather more than we have invented Shakespeare. To accuse Shakespeare of having invented, say, Newt Gingrich or Harold Bloom is not necessarily to confer any dramatic value upon either Gingrich or Bloom, but only to see that Newt is a parody of Gratiano in The Merchant of Venice, and Bloom is a parody of Falstaff. A nouveau historicizer would dismiss that as a politics of identity, but I dare say it was the praxis of the audience at the Globe, and of Shakespeare himself, who gave us Ben Jonson as Malvolio, Kit Marlowe as Edmund, and William Shakespeare as – There you take your choice. The playwrights in Shakespeare are inspired amateurs: Peter Quince, Falstaff and Hal, Hamlet, Iago, Edmund, Prospero – and I suspect that the highly professional Shakespeare has no surrogate in that rather various group. The only parts we know for sure that he acted were the Ghost in Hamlet and old Adam in As You Like It. One gathers he was available to play older men, and we can wonder how many English kings he portrayed. A number of critics suggestively have called Shakespeare a Player King., haunted by images akin to those assumed by Falstaff and Hal when they alternate the role of Henry IV in their improvised skit. Perhaps Shakespeare played Henry IV, we do not know. To be a player clearly was for Shakespeare an equivocal fate, one that involved some social chagrin. We do not know how closely to integrate Shakespeare’s life and his sonnet sequence, but critics have intimated, to me convincingly, that Falstaff’s relation to Hal has a parallel in the poet’s relation, in the Sonnets, to his patron and possible lover, the Earl of Southampton. Whatever it was that Shakespeare experienced with Southampton, it clearly had a negative side, and too searingly reminded him that he was indeed a player and not a king.

Why Shakespeare? He childed as we fathered; he cannot have intended to make either his characters or his audience into his children, but he fathered much of the future, and not of the theater alone, not even of literature alone. Almost the only lasting human concern that Shakespeare can be said to have not affected is religion, whether as praxis or as theology. Though his care was to avoid politics and faith alike, for his-neck’s sake, he has influenced politics considerably, though far less than he has shaped psychology and morals (circumspect as he was to morality, at least in his fashion). As much a creator of selves as of language, he can be said to have melted down and then remolded the representation of the self in and by language. That assertion is the center of this book, and I am aware that it will seem hyperbolical to many. It is merely true, and has been obscured because we now assert far too little for the effect of literature upon life, at this bad time when the university teachers of literature teach everything except literature, and discuss Shakespeare in terms scarcely different from those employed for television serials or the peerless Madonna. What runs on television, or with Madonna, is akin to Elizabethan bear baitings and public executions; Shakespeare indeed was and is popular, but was not ‘popular culture,’ whether then or now, at least not in our curious, current sense of what increasingly has become an oxymoron.

Why Shakespeare? Who could replace him, as a representer of persons? Dickens has something of Shakespeare’s global universalism, but Dickens’s grotesques, and even his more normative figures, are caricatures, more in the mode of Ben Jonson than of Shakespeare. Cervantes is closer to an authentic rival: Don Quixote matches Hamlet, and Sancho Panza could certainly confront Falstaff, but where are Cervantes’s Iago, Macbeth, Lear, Rosalind, Cleopatra? Chaucer, I suspect, comes closest, and Chaucer is Shakespeare’s authentic precursor, more truly influential on Falstaff and Iago than Marlowe (and Ovid) could ever be on any Shakespearean character. Doubtless we read, and even go to the theater, in quest of more than personalities, bust most human beings are lonely, and Shakespeare was the poet of loneliness and of its vision of mortality. Most of us, I am persuaded, read and attend theater in search of other selves, larger and more detailed than any closest friends or lovers seem to be. I hardly think that makes Shakespeare a substitute for life, which, alas, so often seems an inadequate substitution for Shakespeare. Oscar Wilde, with his canny observation that nature imitates Shakespeare, as best as it can, is the proper guide to these matters. The world has grown melancholy, Oscar murmured, because a puppet, Hamlet, was sad. Other poets have made a heterocosm or second nature, Spencer and Blake and Joyce among them. Shakespeare is a third realm, neither nature nor second nature. This third kingdom is imaginal, rather than given or imaginary.

By ‘the imaginal,’ I here mean Shakespeare’s idea of the play, which has been subtly expounded by a number of critics since Anne Barton. Even as a growing uneasiness gradually removed much of Shakespeare’s pride in the theater, an implicit confidence in his own power of characterization partly took the place of a waning contact with his audience. Acting and harlotry blend into each other in Shakespeare’s disillusionment, and he recoils from the mix only to suggest that plays themselves, as deceits, are ghostlike imitations of sordid realities. But what of those greater shadows, the men and the women of the ‘dark comedies,’ the high tragedies, and the tragical comedies that we (not Shakespeare) call ‘late romances?’ To turn against representation is to renew Plato’s polemic against the poets, yet we do not sense any transcendental element in Shakespeare’s dialectical revulsion from shadows. Transcendentalism, in Shakespeare, tends to be available only in its withdrawal and departure, as when we hear the music of the god Hercules abandoning his favorite. Antony. Shakespeare, even at his darkest, is reluctant to abandon his protagonists. We cannot imagine Shakespeare, like Ben Jonson, collecting his own plays in a large folio entitled The Works of William Shakespeare, and yet Prospero is hardly a figure of diminishment, however he chooses to conclude. We do not see the Shakespearean magus very plainly on our stage these days, because more often than not he is presented as a baffled white colonialist who does not know how to cope with a heroic black insurgent (or even two, if George C. Wolfe’s fancy about Ariel as a defiant black woman should prove contagious). Still. Prospero abides as an image of Shakespeare’s pride (somewhat equivocal) in his own magic of creating persons.

Leeds Barroll, in a persuasive revision of Shakespearean chronology, argues that Shakespeare produced King Lear, Macbeth, and Antony and Cleopatra in about a year and two months – in 1606-7. This extraordinary pace, again according to Barroll, was also standard for Shakespeare, who wrote twenty-seven plays in the decade from 1592 to 1602. Still, it is a kind of shock to envision the composition of King Lear, Macbeth, and Antony and Cleopatra in just fourteen months. And yet, each time I read King Lear, I am startled that any single human being could compose so vast a cosmological catastrophe in any time span. I think we are returned to the basis for now unfashionable Bardolatry: we find something preternatural about Shakespeare, as we do about Michelangelo or Mozart. Shakespeare’s facility, marked by his contemporaries, seems to us something more. Whatever the social and economic provocations that animated him, they could scarcely differ, in kind or in degree, from the precisely parallel stimuli upon, say, Thomas Dekker or John Fletcher. The mystery of Shakespeare, as Barroll implies, is not the composition of three tragedies in sixty weeks but that the three comprised Lear, Macbeth, and Antony and Cleopatra.

Leeds Barroll, in a persuasive revision of Shakespearean chronology, argues that Shakespeare produced King Lear, Macbeth, and Antony and Cleopatra in about a year and two months – in 1606-7. This extraordinary pace, again according to Barroll, was also standard for Shakespeare, who wrote twenty-seven plays in the decade from 1592 to 1602. Still, it is a kind of shock to envision the composition of King Lear, Macbeth, and Antony and Cleopatra in just fourteen months. And yet, each time I read King Lear, I am startled that any single human being could compose so vast a cosmological catastrophe in any time span. I think we are returned to the basis for now unfashionable Bardolatry: we find something preternatural about Shakespeare, as we do about Michelangelo or Mozart. Shakespeare’s facility, marked by his contemporaries, seems to us something more. Whatever the social and economic provocations that animated him, they could scarcely differ, in kind or in degree, from the precisely parallel stimuli upon, say, Thomas Dekker or John Fletcher. The mystery of Shakespeare, as Barroll implies, is not the composition of three tragedies in sixty weeks but that the three comprised Lear, Macbeth, and Antony and Cleopatra.

I have been chided by my old friend Robert Brustein, the director of the American Repertory Theatre at Harvard, for suggesting that we might be better off with public readings of Shakespeare, on screen as on stage. Ideally, of course, Shakespeare should be acted, but since he is now almost invariably poorly directed and inadequately played, it might be better to hear him well rather than see him badly. Ian McKellan would be a splendid Richard III, but if his director insists that McKellen portray Richard as Sir Oswald Mosley, the English would-be Hitler, then I would prefer to hear this remarkable actor read the part aloud instead. Laurence Fishburne is an impressive-looking personage, but consider how long one could listen to his reading of Othello’s part aloud. Shakespeare’s texts indeed are somewhat like scores, and need to be adumbrated by performance, but if our theater is ruined, would not public recitation be preferable to indeliberate travesty?

It is a commonplace that there is even more commentary on Shakespeare than there is on the Bible. For us, the Bible is the most difficult of books. Shakespeare is not; paradoxically, he is open to everyone, and provocative to endless interpretation. The prime reason for this, put most simply, is Shakespeare’s endless intelligence. His major characters are rich in multiform qualities, and a mixed few of them abound as intellects: Falstaff, Rosalind, Hamlet, Iago, Edmund. They are more intelligent than we are, an observation that will strike a formalist or historicist critic as Bardolatrous nonsense. But the creatures directly reflect their creator: his intelligence is more comprehensive and more profound than that of any other writer we know. The aesthetic achievement of Shakespeare cannot be separated from his cognitive power. I suspect that this accounts for his mixed effect on philosophers: Hegel and Nietzsche celebrated him, but Hume and Wittgenstein regarded him as overesteemed, possibly because a human being as intelligent as Falstaff or Hamlet seemed not possible to them. Falstaff is at once a cosmos and a person; Hamlet, more enigmatic, is a person and a potential king. The equivocal Machiavel, Prince Hal, is certainly a person, and becomes a formidable king, but he is considerably less of a world-in-himself than are Falstaff and Hamlet, or even Rosalind. Iago and Edmund each is an abyss in himself, fevering to a false creation.

A.D. Nuttall, one of my heroes of Shakespearean criticism, wonderfully tells us that Shakespeare was not a problem solver, and cleared up no difficulties (which may be why Hume and Wittgenstein undervalued the maker of Falstaff and Hamlet). Like Kierkegaard, Shakespeare enlarges our vision of the enigmas of human nature. Freud, wrongly desiring to be a scientist, gave his genius away to reductiveness. Shakespeare does not reduce his personages to their supposed pathologies or family romances. Freud, wrongly desiring to be a scientist, gave his genius away to reductiveness. Shakespeare does not reduce his personages to their supposed pathologies or family romances. In Freud, we are overdetermined, but always in much the same way. In Shakespeare, as Nuttall argues, we are overdetermined in so many rival ways that the sheer wealth of overdeterminations becomes a freedom. Indirect communication, the mode of Kierkegaard, so well expounded by Roger Poole, was learned by Kierkegaard from Hamlet. Perhaps Hamlet, like Kierkegaard, came into the world to help save it from reductiveness. If Shakespeare brings us a secular salvation, it is partly because he helps ward off the philosophers who wish to explain us away, as if we were only so many muddles to be cleared up.

I remarked earlier that we ought to give up the failed quest of trying to be right about Shakespeare, or even the ironic Eliotic quest of trying to be wrong about Shakespeare in a new way. We can keep finding the meanings of Shakespeare, but never the meaning: It is like the search for ‘the meaning of life.’ Wittgenstein, and the formalist critics, and the theatricalists, and our current historicizers, all join in telling us that life is one thing and Shakespeare another, but the world’s public, after four centuries, thinks otherwise, and they are not easily refuted. Ben Jonson, Shakespeare’s shrewdest friend and contemporary, began by insisting that Shakespeare wanted art, but after Shakespeare’s death, Jonson felt differently. Advising the actors on how to edit the First Folio of Shakespeare, Jonson must have read about half of the plays for the first time, and he seems to have come around to Shakespeare’s own view that ‘the art itself is nature.’ David Riggs, Jonson’s biographer, defends Jonson from Dryden’s accusation of insolence toward Shakespeare, and shows rather that the more neoclassical poet-playwright changed his mind when the full range of Shakespeare was made available to him. What Jonson discovered, and celebrated, is what common readers and common playgoers keep discovering, which is that Shakespeare’s personages are so artful as to seem totally natural.

Nothing is more difficult for scholars of Shakespeare to apprehend and acknowledge than his cognitive power. Beyond any other writer – poet, dramatist, philosopher, psychologist, theologian – Shakespeare thought everything through again for himself. This makes him as much the forerunner of Kierkegaard, Emerson, Nietzsche, and Freud as of Ibsen, Strindberg, Pirandello, and Beckett. Working as a playwright under Elizabeth I, and then under James I, Shakespeare necessarily presents his thoughts obliquely, only rarely allowing himself a surrogate or spokesperson among his dramatic personages. Even when one may appear, we cannot know who it is. The late novelist Anthony Burgess judged Sir John Falstaff to be Shakespeare’s prime surrogate. Myself a devout Falstaffian, with a passion against the novelists who lack gratitude for Falstaff, I want to think that Burgess was right, but I cannot know this. I tend to find Shakespeare in Edgar, perhaps because I locate Christopher Marlowe in Edmund, but I do not wholly persuade myself. It may be that no character – not Hamlet, nor Prospero, nor Rosalind – speaks ‘for’ Shakespeare himself. Perhaps the extraordinary voice we hear in the Sonnets is as much a fiction as any other voice in Shakespeare, though I find that very difficult to believe.

Shakespeare, canny and uncanny, played with almost every ‘received’ concept that was available to him, but may have been persuaded by none of them whatsoever. If you reread his plays incessantly, and ponder every performance you attend, you are not likely to think of him either as a Protestant or as a Catholic, or even as a Christian skeptic. His sensibility is secular, not religious. Marlowe, the ‘atheist,’ had a more religious temperament than Shakespeare possessed, while Ben Jonson, though as secular a dramatist as Shakespeare, was personally more devout (by fits and starts, anyway). We know that Jonson preferred Sir Francis Bacon to Montaigne; we suspect that Shakespeare might not have agreed with Jonson. Montaigne was a kind of tenuous link between Shakespeare and Moliere: Montaigne would be all that they might have had in common. His motto, ‘What do I know?’ is a fit epigraph for both playwrights.

Whatever it was that Shakespeare knew (and it seems not less than everything), he had generated most of it himself. His relation to Ovid and to Chaucer is palpable, and his contamination by Marlowe was considerable, until it was worked out by the triumphant emergence of Falstaff. Except for those three poets, and for a purely allusive relationship to the Bible, Shakespeare did not rely on authorities, or on authority. When we confront the greatness of his tragedies – Hamlet, Othello, King Lear, Macbeth, Antony and Cleopatra – we are alone with Shakespeare. We enter a cognitive realm where our moral, emotional, and intellectual preconceptions will not aid us in apprehending sublimity. When acute scholars pratfall into the trap of assuring us that Shakespeare somehow trusted in ‘a universal moral order which cannot finally be defeated,’ they lose their way in King Lear or Macbeth, which are set in no such order. The man Shakespeare, cautious and diffident, wrote only one play taking place in Elizabethan England, the not-very-subversive farce The Merry Wives of Windsor. Shakespeare was too circumspect to set a play in Jacobean England or Scotland: King Lear and Macbeth keep an eye upon James I, while Antony and Cleopatra avoids any too close resemblances to James’s rather dubious court. The death of Christopher Marlowe was a lesson Shakespeare never forgot, while the torture of Thomas Kyd and the incarnation of Ben Jonson doubtless also hovered always in Shakespeare’s consciousness. There is little authentic evidence, in the plays, that Shakespeare strove either to uphold or to subvert, however covertly, the established order.

Whatever it was that Shakespeare knew (and it seems not less than everything), he had generated most of it himself. His relation to Ovid and to Chaucer is palpable, and his contamination by Marlowe was considerable, until it was worked out by the triumphant emergence of Falstaff. Except for those three poets, and for a purely allusive relationship to the Bible, Shakespeare did not rely on authorities, or on authority. When we confront the greatness of his tragedies – Hamlet, Othello, King Lear, Macbeth, Antony and Cleopatra – we are alone with Shakespeare. We enter a cognitive realm where our moral, emotional, and intellectual preconceptions will not aid us in apprehending sublimity. When acute scholars pratfall into the trap of assuring us that Shakespeare somehow trusted in ‘a universal moral order which cannot finally be defeated,’ they lose their way in King Lear or Macbeth, which are set in no such order. The man Shakespeare, cautious and diffident, wrote only one play taking place in Elizabethan England, the not-very-subversive farce The Merry Wives of Windsor. Shakespeare was too circumspect to set a play in Jacobean England or Scotland: King Lear and Macbeth keep an eye upon James I, while Antony and Cleopatra avoids any too close resemblances to James’s rather dubious court. The death of Christopher Marlowe was a lesson Shakespeare never forgot, while the torture of Thomas Kyd and the incarnation of Ben Jonson doubtless also hovered always in Shakespeare’s consciousness. There is little authentic evidence, in the plays, that Shakespeare strove either to uphold or to subvert, however covertly, the established order.

The Sonnets seem to manifest a profound chagrin at being what we call an entertainer, but I think that Shakespeare might have felt even more chagrin had he found himself to be what we call a moralist. Insofar as Marlowe was his forerunner, Shakespeare desired to hold an audience even more firmly than Marlowe held them. Shakespeare railed against the actors, but never – like Ben Jonson – against the audience. Jonson’s trauma was that his tragedy Sejanus had been hooted off the stage at the Globe. Shakespeare, acting in the play, must have reflected that he had had no similar experience, and he never would. His audience loved Falstaff and Hamlet from the start. Doubtless, the groundlings hissed Sejanus for some of the same reasons that caused Jonson to be summoned before the Council, there to be accused of ‘popperie and treason,’ but probably they also found it as boring as we do. Jonson – a magnificent comic playwright in Volpone, The Alchemist, and Bartholemew Fair – alas was a pedant of a tragedian. Shakespeare, who bored none, took care not to offend ‘the virtuous’ in his England; that came later, and has achieved it’s apotheosis now, in our humorless academy. That Shakespeare reigns still as the world’s universal entertainer, multicultural and amazingly metamorphic, returns us to the unsolved secret of what it is in him, that transcends history.

To call Shakespeare a ‘creator of language,’ as Wittgenstein did, is insufficient, but to call Shakespeare also a ‘creator of characters,’ and even a ‘creator of thought’ is still not enough. Language, character, and thought all are part of Shakespeare’s invention of the human, and yet the largest part is the passional. Ben Jonson remained closer to Marlowe’s mode than to Shakespeare’s in that Jonson’s personages also are cartoons, caricatures without inwardness. That is why there is no intergenerational contest in Jonson’s plays, no sense of what Freud called ‘family romances.’ The deepest conflicts in Shakespeare are tragedies, histories, romances, even comedies: of blood. When we consider the human, we think first of parents and children, brothers and sisters, husband and wives. We do not think of these relationships in terms of Homer and of Athenian tragedy, or even of the Hebrew Bible, because the gods and God are not primarily involved. Rather, we think of families as being alone with one another, whatever the social contexts, and that is to think in Shakespearean terms.

Change – of fortune, and in time –is Shakespeare’s largest commonplace. Death, the final form of change, is the overt concern of Shakespeare’s tragedies and histories, and the hidden preoccupation of his comedies. His tragicomedies – or romances, as we now call them, treat death more originally even than do his high tragedies. Perhaps all sonnets, being ultimately erotic, tend to be elegiac; Shakespeare’s appear as the shadows of death itself. Death’s ambassador to us uniquely is Hamlet; no other figure, fictive or historic, is more involved with that undiscovered country, unless you desire to juxtapose Jesus with Hamlet. Whether you subsume Shakespeare under nature or art, his peculiar distinction prevails: he teaches us the act of dying. Some have said this is because Shakespeare approximates a secular scripture. It does seem more adequate, to me, to take Shakespeare (or Montaigne) as such a text than it would be to take Freud or Marx or Franco-Heideggerians or Franco-Nietzscheans. Shakespeare, almost uniquely is both entertainment and wisdom literature. That the most pleasure-giving of all writers should also be the most intelligent is almost a bewilderment to us. So many of our ‘cloven fictions’ (as William Blake called them are dissolved by Shakespeare that even a brief listing may be instructive: affective versus cognitive; secular versus sacred; entertainment versus instruction; roles-for-actors versus characters and personalities; nature versus art; ‘author’ versus ‘language’; history versus fiction; context versus text; subversion versus conservation. Shakespeare, in cultural terms, constitutes our largest contingency; Shakespeare is the cultural history that overdetermines us. This complex truth renders vain all our attempts to contain Shakespeare within concepts provided by anthropology, philosophy, religion, politics, psychoanalysis, or Parisian ‘theory’ of any sort. Rather, Shakespeare contains us; he always gets there before us, and always waits for us, somewhere up ahead.

There is a fashion among some current academic writers on Shakespeare that attempts to explain away his uniqueness as a cultural conspiracy, an imposition of British imperialism, and so a weapon of the West against the East. Allied to this fashion is an even sillier contention: that Shakespeare is no better or worse a poet-playwright than Thomas Middleton or John Webster. After this, we are taken over the verge into lunacy. Middleton wrote Macbeth, Sir Francis Bacon or the Earl of Oxford wrote all of Shakespeare, or whole committees of dramatists wrote Shakespeare, commencing with Marlowe and concluding with John Fletcher. Though academic feminism, Marxism, Lancanianism, Foucaultianism, Derrideanism, and so on are more respectable (in the academies) than the Baconians and Oxfordians, it is still the same phenomenon, and contributes nothing to a critical appreciation of Shakespeare. This book commenced by turning away from almost all current Anglo-American writing about, and teaching of, Shakespeare; I mentioned it as rarely as possible, because it cannot aid any open and honest reader or playgoer in the quest to know Shakespeare better.

The wheel of fortune, time, and change turns perpetually in Shakespeare, and accurate perception of him must begin by viewing these turnings, upon which Shakespeare’s characters are founded. Dante’s characters can evolve no further; Shakespeare’s, as I have noted, are much closer to Chaucer’s and seem to owe more to Chaucer’s mutable visions of men and women than to anyone else’s, including biblical portrayals or those of Shakespeare’s favorite Latin poet, Ovid. Tracing Ovid’s effect upon Shakespeare in his study The Gods Made Flesh, Leonard Barkan observes, ‘Many of the great figures of Ovid’s poem define themselves by their struggle to invent new languages.’ Metamorphoses in Shakespeare are almost always related to the playwright’s endless quest to find distinct language for every major and many a minor character, language that can change even as they change, wander even as they wander. Turning around, in Shakespeare, frequently takes on the traditional image of wheeling, the wheel sometimes being Fortune’s emblem of extravagance: of roaming beyond limits.

Shakespeare’s own audiences chose Falstaff as their favorite, even above Hamlet. Fortune’s wheel seems to have little relevance to others; Falstaff is ruined by his hopeless, misplaced paternal love for Prince Hal. Hamlet dies after a fifth act in which he has transcended all his earlier identities in the play. Falstaff is thus love’s fool, not fortune’s, while Hamlet can only be regarded as his own fool or victim, replacing his father surrogate, the clown Yorick. It is appropriate that the antithetical figures of Lear and Edmund both invoke the image of the wheel, but to opposite effects and purposes. Shakespeare’s plays are the wheel of our lives, and teach us whether we are fools of time, or of love, or of fortune, or of our parents, or of ourselves.”

———-

My next (and last post) Thursday evening/Friday morning.